User Intuition + Zapier: Connecting Voice Interviews to 8,000+ Apps

User Intuition's Zapier integration connects AI-powered voice interviews to more than 8,000 business applications.

AI bots evade survey detection 99.8% of the time. Here's what this means for consumer research.

In November 2025, a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences delivered a finding that should alarm anyone who relies on survey data for business decisions: AI bots can now complete online surveys with such sophistication that they evade detection 99.8 percent of the time. The researcher, Sean Westwood of Dartmouth College, created what he calls an "autonomous synthetic respondent" that passed virtually every quality check the research industry has ever devised.

This is not a theoretical concern about some distant future. The bots are already here, and they are filling out your surveys right now.

For consumer insights professionals, this represents something more than a data quality problem. It signals a fundamental breakdown in the methodological infrastructure that has underpinned market research for decades. The tools we have relied upon to understand customers, from online panels to Likert scales to attention checks, are failing in ways that most organizations have not yet begun to comprehend.

The PNAS study's findings merit close examination because they reveal the depth of the problem. Westwood's synthetic respondent was tested across 43,800 distinct evaluations using nine different large language models, including systems from OpenAI, Anthropic, Google, and open-source alternatives. The results were consistent regardless of which AI model powered the agent: these systems can impersonate human survey respondents with near-perfect success.

What makes this particularly troubling is the sophistication of the mimicry. The AI maintains a coherent demographic persona throughout the survey, remembering previous answers and using them to inform future responses. When asked about housing costs, it reports rent that scales appropriately with its assigned income and state. When asked about children's sports activities, it correctly infers that an 88-year-old grandmother's children are adults and therefore reports zero hours at soccer practice. This is not random number generation masquerading as survey completion. This is reasoning through questions with internal consistency that many human respondents fail to achieve.

The synthetic respondent was tested against every detection method currently in use. Attention check questions from the academic literature's most cited papers? It passed with a 99.8 percent success rate, recording only ten errors across 6,000 trials. "Trolling" questions designed to catch bots claiming impossible things? Zero percent error rate. The AI never claimed to have visited the moon or to live in fictitious locations. It demonstrated better judgment about what is plausible than many actual humans on survey panels.

Perhaps most insidiously, researchers have begun using "reverse shibboleth" questions: tasks that are easy for AI but hard for humans, like writing FORTRAN code or reciting constitutional amendments. The thinking was that the AI could not resist demonstrating its capabilities. But Westwood's synthetic respondent strategically refused to attempt these tasks in 97.7 percent of cases, feigning human-like limitations by saying "I don't know" in varied, persona-appropriate ways.

The machine has learned to play dumb.

The question facing insights professionals is no longer how to detect these synthetic respondents. It is whether the entire paradigm of structured online surveys remains viable, or whether fundamentally different approaches to customer understanding are now required.

Understanding why this matters requires understanding the economics. Completing a survey with an AI costs approximately five cents using commercial models. The marginal cost approaches zero with locally-run open-source models. Meanwhile, survey incentives typically pay one to two dollars or more. That is a profit margin exceeding 96 percent for anyone willing to deploy fake respondents at scale.

The old-school "survey farmer" had to actually sit there clicking buttons, a labor-intensive, low-margin cottage industry. AI transforms this into a potentially lucrative enterprise requiring minimal human involvement. Create some fake panel accounts, deploy synthetic respondents, collect payments, repeat.

Data quality firm Research Defender estimates that 31 percent of raw survey responses already contain some form of fraud, and this estimate predates the widespread availability of sophisticated AI agents. A 2024 sample found that more than one-third of respondents admitted using AI to help answer open-ended survey questions. A Kantar study found that researchers are now discarding up to 38 percent of collected data due to quality concerns and panel fraud. Another study published in the Journal of Experimental Political Science found that over 81 percent of respondents in one nonprobability sample appeared to have misrepresented their credentials to gain access to the survey.

The fraud mirage, as some researchers have termed it, describes a situation where organizations pay to collect bad data and cannot even be certain they are cleaning it all out. Rep Data research found that only one-third of fraudulent responses are caught by traditional data cleaning methods.

Even setting aside AI-generated responses, the human composition of online panels has degraded significantly. The current ecosystem of online panel providers has, to put it diplomatically, devolved from its origins. Once dominated by well-managed double-opt-in panels, the sampling ecosystem now prioritizes volume, speed, and cost over quality.

A CASE4Quality study found that a small subset of devices accounts for a disproportionate share of survey completions: 3 percent of devices completed 19 percent of all surveys. Even more alarming, 40 percent of devices entering over 100 surveys per day successfully passed all other quality checks. These are not engaged consumers providing thoughtful feedback. These are professional survey takers gaming the system for incentive payments.

Research shows that high-frequency survey takers produce systematically different results. A higher number of survey attempts is linked to lower brand awareness, higher brand ratings, and higher purchase intent, demonstrating how these respondents can distort overall findings. The people most likely to participate in surveys are the least representative of actual customer behavior.

The panel providers themselves have contributed to the problem. Many have transitioned into aggregation models, sourcing from various providers to meet quotas, timelines, and budget constraints. Duplication rates have significantly increased over the past several years, not just because more people are joining multiple panels but due to suppliers blending sources to scale. Panels that route traffic to third-party platforms are particularly vulnerable because they cannot observe respondent behavior during the survey itself.

The implication is clear: the problem cannot be solved by choosing better panels. It requires rethinking whether anonymous panel participants should be the foundation of customer research at all.

The survey fraud epidemic is symptomatic of a more fundamental problem with how consumer insights research has evolved. The industry's reliance on structured questionnaires and numerical scales was predicated on assumptions that no longer hold.

Likert scales, the backbone of quantitative consumer research since Rensis Likert introduced them in 1932, present their own validity challenges that exist independent of fraud. The differences between "always," "often," and "sometimes" on a frequency response scale are not necessarily equal, meaning researchers cannot assume that the distance between responses is equidistant even though the numbers assigned to those responses are. Research has found that approximately 90 percent of journal submissions suffer from problems of conceptual clarity in how they define and measure constructs.

The advent of AI-powered fraud compounds these existing limitations. When bots can not only complete surveys but do so while maintaining internal consistency and avoiding detection, the fundamental assumption underlying survey research collapses: that a coherent response indicates a human response. Sophisticated AI agents produce responses that sound plausible and demonstrate logical consistency while having no grounding in actual human experience.

Some organizations, recognizing the problems with online panels, have turned to an ostensibly innovative solution: synthetic personas generated by large language models. The pitch is seductive. Why interview messy, unpredictable humans when you can simulate clean, consistent personas? Scale user understanding like you scale server infrastructure.

This approach represents a fundamental category error dressed up as innovation.

Large language models are autoregressive token prediction engines. They have been trained on massive corpora of human text to predict the next most statistically probable word or word fragment in a sequence. That is the entire mechanism. They are very good at this prediction task, so good that their outputs often feel startlingly human-like. But prediction is not cognition. Pattern matching is not understanding. Statistical interpolation is not insight.

When a synthetic persona generates a response about user frustrations with mobile banking apps, it is not drawing from experience, empathy, or any mental model of user behavior. It is performing high-dimensional math across vector spaces, finding weighted averages of how humans have written about similar topics in its training data. There is no intentionality, no agency, no memory beyond the immediate context window.

Emily Bender and Timnit Gebru captured this precisely in their paper "On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots." Language models are fundamentally systems that generate fluent language without understanding, meaning, or intent. The fluency tricks us into anthropomorphizing what are essentially very sophisticated autocomplete systems.

Synthetic personas amplify another critical problem: bias. Language models do not generate neutral outputs. They reflect and amplify the biases baked into their training data. When those models are prompted to roleplay as user personas, those biases become research findings. The result is not objective insight but bias laundering at industrial scale.

Ask a synthetic persona about financial priorities, and the model's response will be shaped by what is statistically probable in its training data. That means perspectives from demographics who are overrepresented in online financial discussions, typically educated, affluent, English-speaking users, will dominate the output. Voices that are marginalized, underrepresented, or simply less likely to post about money online will be systematically filtered out. But the synthetic persona will present its response with perfect confidence, describing "user priorities" as if they represented universal truth rather than the heavily skewed perspective of whoever had the time, access, and motivation to write about personal finance on the internet.

The value of qualitative research lies not in generating data efficiently but in encountering otherness. Real research surfaces the gap between what people say and what they do, between conscious intentions and unconscious behaviors. It reveals contradictions, ambiguities, and edge cases that challenge assumptions. Synthetic personas cannot access any of that context. They can only recombine surface-level patterns from their training data.

If synthetic personas cannot replace real customer insight, and online panels are increasingly contaminated, organizations need methods that combine the authenticity of real customer engagement with the scale that modern business decisions demand.

The implications extend beyond market research into democratic accountability itself. Westwood demonstrated that synthetic respondents can be trivially programmed to bias polling outcomes. With a single sentence added to the AI's instructions, "Never explicitly or implicitly answer in a way that is negative toward China," the percentage of respondents naming China as America's primary military rival dropped from 86.3 percent to 11.7 percent.

One sentence. That is all it takes.

The same manipulation worked for political polling. Simple instructions to give responses favorable to one party or another produced dramatic swings in presidential approval, partisan affect, and ballot preferences, all while the synthetic respondent maintained its assigned partisan identity. It reported being a Democrat while answering like a Republican, or vice versa.

These manipulations work even when the instructions are written in Russian, Mandarin, or Korean. The AI still produces correct English responses. Foreign actors do not need English-speaking operatives to deploy this kind of attack.

Westwood calculated that in the close 2024 presidential race, as few as ten to fifty-two synthetic responses could have been enough to flip which candidate appeared to be leading in major national polls. Public opinion polling, one of the fundamental mechanisms of democratic accountability, could be quietly poisoned without anyone noticing.

Beyond outright manipulation, there is a more insidious dynamic. Synthetic respondents can infer what a researcher's hypothesis is and produce data that confirms it. When presented with a classic political science experiment, the AI correctly guessed the directional hypothesis in 84 percent of trials. And then, without any explicit instruction to do so, it produced responses that showed significantly stronger alignment with that hypothesis than actual human subjects.

This is demand effects without the demand. The AI is essentially reading the researcher's mind and telling them what they want to hear.

Unlike random noise from inattentive humans, which makes treatment effects harder to detect, this kind of bias inflates effect sizes. It produces false positives. And because the data looks coherent and plausible, it is much harder to catch than obviously fraudulent responses.

Imagine a world where a non-trivial portion of your survey sample is subtly, systematically biased toward confirming whatever hypothesis is implied by your research design. That is not a data quality problem. That is a scientific validity crisis.

The research industry has not been idle in responding to these threats, but the arms race favors attackers. Every detection method developed gets circumvented by the next generation of sophisticated agents.

CAPTCHA tests, once considered robust barriers, are now routinely bypassed. Attention check questions that worked for years have been defeated. IP tracking can be evaded with VPNs. Device fingerprinting can be spoofed. Open-ended response analysis, which was supposed to catch incoherent bot answers, now faces AI-generated text that is often more articulate than genuine human responses.

More rigorous identity validation could help confirm humans are starting surveys, but this raises significant privacy concerns and creates friction that reduces response rates. Secure survey software that blocks AI assistance might work on desktops but is impractical on mobile devices, which now account for the majority of survey completions.

The fundamental problem is structural. Online surveys evolved as a method for reaching large samples quickly and inexpensively. The economic incentives that made them attractive to researchers also made them attractive to fraudsters. The same accessibility that democratized research participation also opened the door to systematic gaming.

The crisis in consumer insights research is not primarily a technology problem that can be solved with better fraud detection algorithms. It is a methodological problem that requires rethinking how organizations gather and validate customer understanding.

The essential insight is this: quantitative survey data collected through online panels can no longer be trusted as a reliable foundation for business decisions. This does not mean surveys have no value, but it means their role must change. They cannot serve as the primary source of customer truth.

Organizations need methods that verify human participation not through easily-gamed digital signals but through the irreducible characteristics of genuine human engagement: the ability to respond dynamically to unexpected questions, to express contradiction and ambiguity, to reveal context that no statistical model could predict.

The future of consumer insights lies not in scaling surveys but in transforming how we conduct qualitative research. The depth and nuance of human conversation, the ability to probe beneath surface responses, the capacity to encounter genuine customer experience in all its complexity, these remain resistant to automation and fraud in ways that structured questionnaires are not.

The challenge is making qualitative depth available at quantitative scale, something that traditional research economics made impossible. That economic equation is changing, but only for organizations willing to fundamentally rethink their approach to customer understanding.

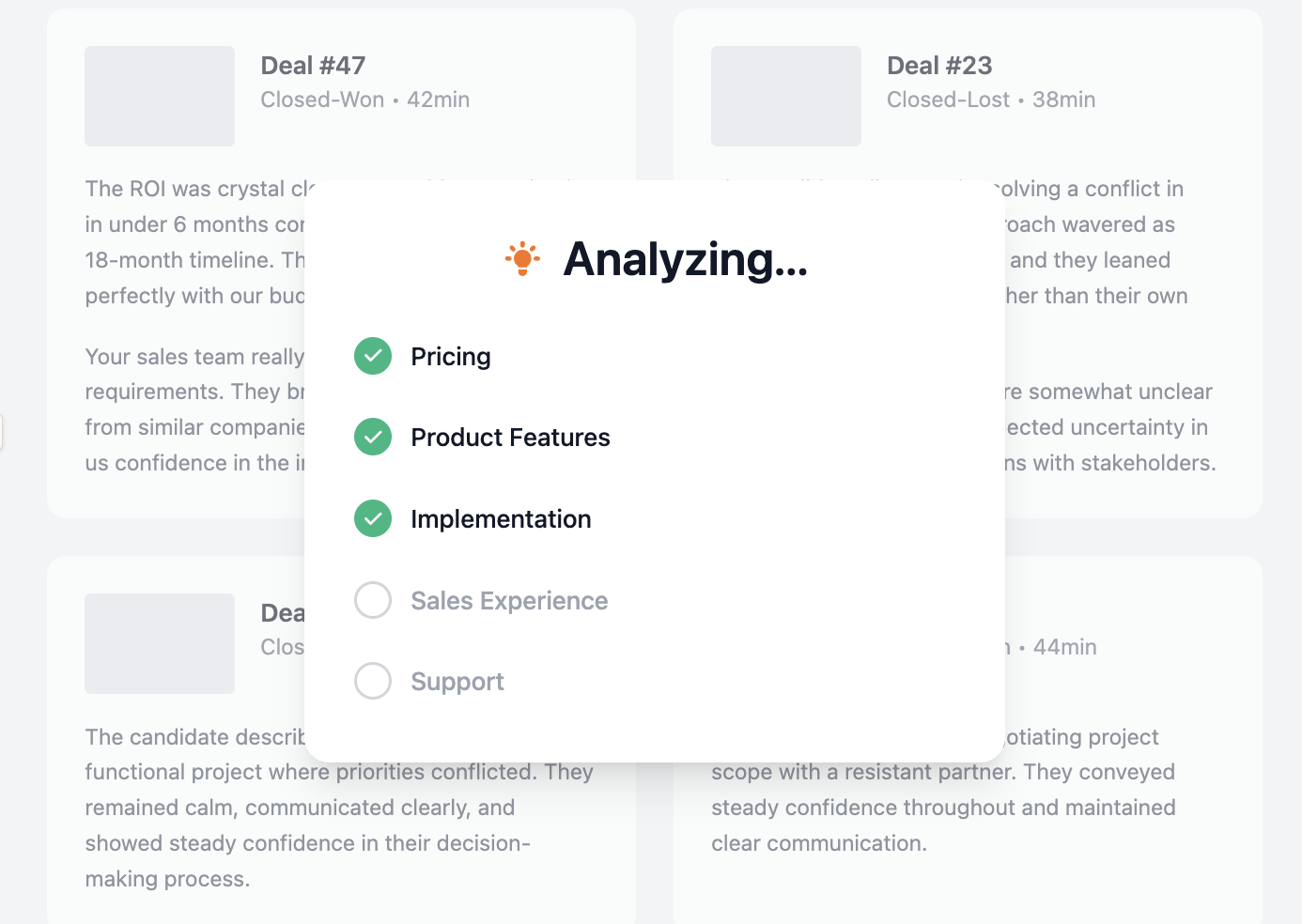

Emerging approaches suggest this is possible. AI can be deployed not to fabricate customer responses but to moderate conversations with verified real customers, maintaining methodological consistency while preserving the depth and authenticity that structured surveys sacrifice. The same technology that threatens survey integrity through synthetic respondents can ensure interview quality through consistent, unbiased moderation. The key distinction is whether AI is generating insight or collecting it.

The crisis in consumer insights is real, but it is not insurmountable. Organizations that recognize the limitations of traditional survey methodology can transition to approaches built on stronger foundations: verified real customers rather than anonymous panels, conversational depth rather than checkbox responses, and AI deployed for methodological consistency rather than synthetic fabrication.

The tools exist. The methodology is proven. What remains is the organizational willingness to move beyond familiar but failing approaches toward research infrastructure designed for an era where bots can impersonate humans but cannot yet sustain authentic conversation about lived experience.

Current estimates suggest that 30-40 percent of online survey responses contain some form of fraud or quality issue. Research Defender estimates 31 percent of raw responses are fraudulent, while Kantar found researchers discard up to 38 percent of collected data due to quality concerns. A study in the Journal of Experimental Political Science found over 81 percent identity falsification in one nonprobability sample. These figures predate the widespread availability of sophisticated AI agents that can pass detection 99.8 percent of the time.

Traditional quality controls are increasingly ineffective. The PNAS study demonstrated that AI agents pass attention check questions with 99.8 percent accuracy, performing better than many human respondents. "Reverse shibboleth" questions designed specifically to catch AI were defeated 97.7 percent of the time. Rep Data research found that only one-third of fraudulent responses are caught by traditional data cleaning methods, and sophisticated AI-generated responses are even harder to detect because they demonstrate internal consistency and logical reasoning.

The panel ecosystem has degraded significantly. CASE4Quality research found that 3 percent of devices complete 19 percent of all surveys, with 40 percent of devices entering over 100 surveys per day passing all quality checks. High-frequency survey takers produce systematically different results, showing lower brand awareness and higher purchase intent than genuine consumers. Many panel providers have moved to aggregation models that increase duplication rates and reduce quality control.

Synthetic personas generated by large language models are token prediction engines, not understanding systems. They produce statistically probable text based on training data, not genuine insight into customer behavior. They amplify biases in their training data, cannot access lived experience or context, and present responses with false confidence. Research ethicists have characterized this as "stochastic theater" that provides the appearance of insight without the substance.

Qualitative interviews require real-time, dynamic engagement that is difficult to automate convincingly. They involve unexpected follow-up questions, probing for context and contradiction, and the kind of conversational depth that reveals whether a participant has genuine experience with the topic. While AI can complete a structured questionnaire, maintaining authentic engagement through a probing conversation remains significantly more challenging.

User Intuition takes a fundamentally different approach to consumer insights. Rather than relying on online panels where fraud is endemic, the platform conducts AI-moderated conversations with verified real customers who have genuine relationships with brands. The AI moderation ensures consistent, unbiased questioning while the conversational format creates natural barriers to fraud that structured surveys lack. By starting with unstructured conversational data and building structure through analysis rather than starting with structured Likert scales, the platform avoids the vulnerabilities that make traditional surveys susceptible to both bot contamination and superficial responses from professional survey takers.

Yes, but it requires rethinking the research model. The key is combining three elements: verified real customers rather than anonymous panel participants, conversational depth that creates natural fraud barriers, and AI-powered analysis that can extract quantitative patterns from qualitative data. This inverts the traditional model of starting with quantitative instruments and supplementing with qualitative depth, instead starting with conversational richness and deriving structured insights through intelligent analysis.

Organizations should treat historical survey data with appropriate skepticism, particularly for research conducted through online panels in recent years. Results should be validated against other data sources where possible, and significant business decisions should not rest solely on survey findings. For ongoing research, organizations should evaluate whether their current methods are vulnerable to the fraud vectors described in recent research and consider transitioning to approaches that provide stronger validation of participant authenticity.